Why?

- Largely due to interest and for educational/academic purposes

- Also because I wanted to know if it was possible

How?

- Making a network was much harder than expected, although when I went into it I didn’t really know what to expect.

- I have attempted to document the process here.

What?

- I have got my own ASN (Autonomous System Number) from RIPE NCC.

- I have got my own /48 IPv6 PA range

- I have configured BGP with Bird2 to route traffic to my cloud server.

- I have used Krill for RPKI signing to make my routes trusted.

Constraints

- Cost

- I’m a student, not a multinational company. I didn’t really have a budget for this but I also didn’t want to be spending the £1k+ to become an LIR with RIPE.

- Time

- I’m in full-time education doing my A-levels and I have a part time job as well. I’d love to spend all day every day working on cool projects like this, but realistically that was never going to happen.

- Skill

- Whilst I’ve always considered myself technically skilled, and I use systems like Linux daily, have quite a background in things like DNS I had never done anything like this. All of this was new to me and I was learning on the job. Before I started, I had never heard of RIPE, IANA, RIRs, LIRs, PA/PI IPs, RPKI and I had never really touched anything to do with BGP.

Advantages

- Luckily I had a few advantages going into this

- An annoyingly long patience

- Some of this debugging took hours and was either undocumented entirely or the documentation was obscure and difficult to understand. But I had a keyboard and a caffeine fuelled determination to keep going.

- Some relevant experience

- I do study computer science, so a lot of concepts are not new to me. I knew what BGP was, I had ideas of lots of concepts such as the wandering trader problem and OSI model - all of which did help to contextualise things.

- Some of this was comparable to how DNS systems work, so I could draw on that knowledge.

- An annoyingly long patience

Requirements

- Now this is all over, what did I need?

- A cloud server (or any server really) from a provider that offers BGP. I used Frantech’s BuyVM, but I hear over providers such as Vultr offer similar services for free as well.

- £30

- Technical knowledge

- A couple of hours

Disclaimer

- This article includes many major simplifications and is written from the perspective of an amateur exploring a lot of this for the first time. Please excuse this, and feel free to discuss changes or report issues to me.

Special Thanks

- This project would not have been possible without Lagrange Cloud, RIPE NCC, Frantech Solutions and NLNETLabs

- Thank you to all the amazing people at these organisations for their help and resources.

So how exactly does one gain an ASN?

- Good question. Getting your hands on an ASN isn’t as difficult as it might sound, but it also isn’t super easy.

- I found a helpful site that contained some LIRs who were offering an ASN registration service.

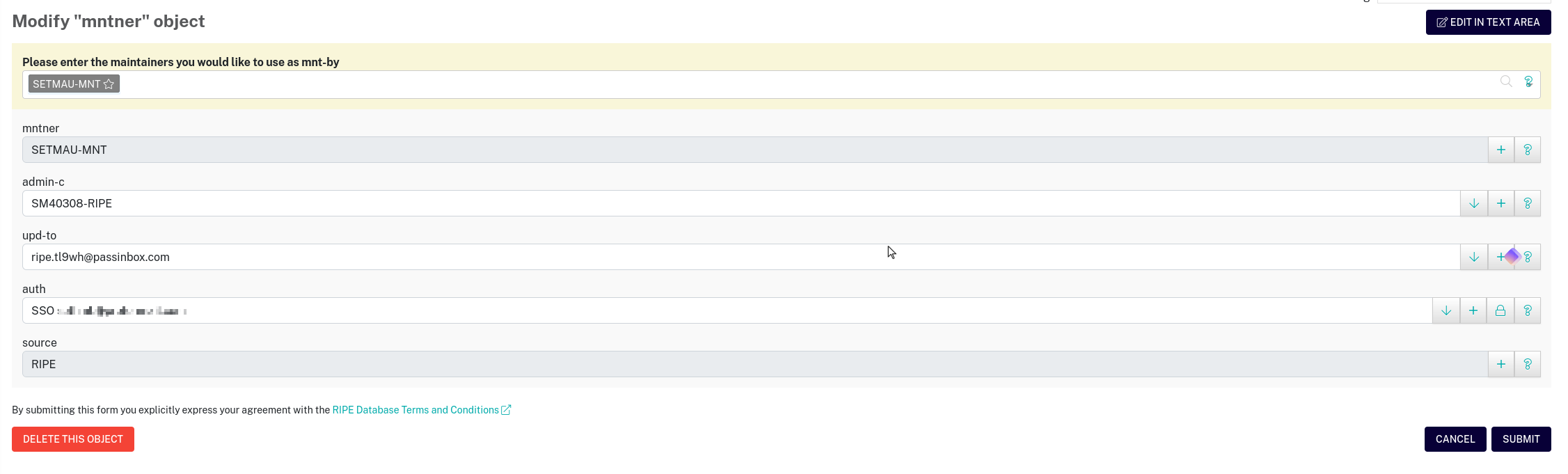

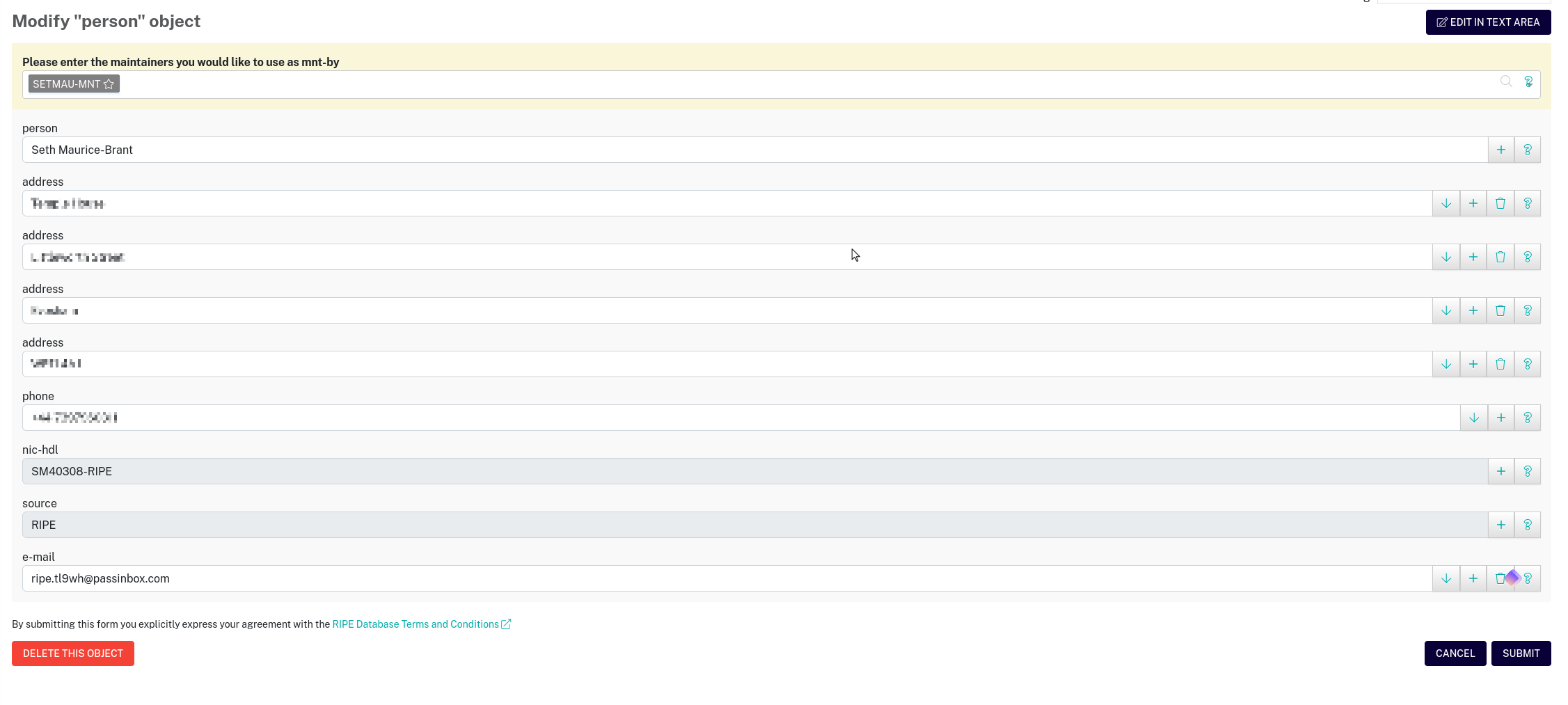

- Before applying, I made some objects on the RIPE database. This is documented alongside the rest of my RIPE objects further down.

- I initially reached out to Freetransit, but spent about a week and a half trying to sign some paperwork before I gave up with them.

- Then I decided to go for Lagrange Cloud as they were based in the UK and had a similar price. Lagrange had a much more automated process that I completely in about 5 minutes.

- I did have a few options to consider throughout the process such as PI or PA IP blocks.

- PA

- Provider Aggregated

- You have less control of the IP range

- It’s cheap

- PI

- Provider Independent

- You have full control of the IP range

- It is not cheap

- PA it was

- My /48 block of IPv6 comes to about £7/year with the first year free. That’s a total of 65,536 IPs. I think that’ll be enough for me.

- PA

- Lagrange then submitted an application to the RIPE NCC on my behalf, who approved my request for an ASN and an IPv6 (PA) block within a couple of days.

Umm, what now?

- So being the highly prepared individual I am, I had no clue what to do next.

- I knew that I had the resources allocated which was what I thought the hard part would be.

- It wasn’t the hard part.

- I logged into my shiny new Frantech server and got to Googling

- The way I saw it, there were 2 viable cloud routing programs.

- Bird (BIRD Internet Routing Daemon)

- FRRouting

- They both seemed like possibilities, and I did give both a shot but in the end I decided to use Bird.

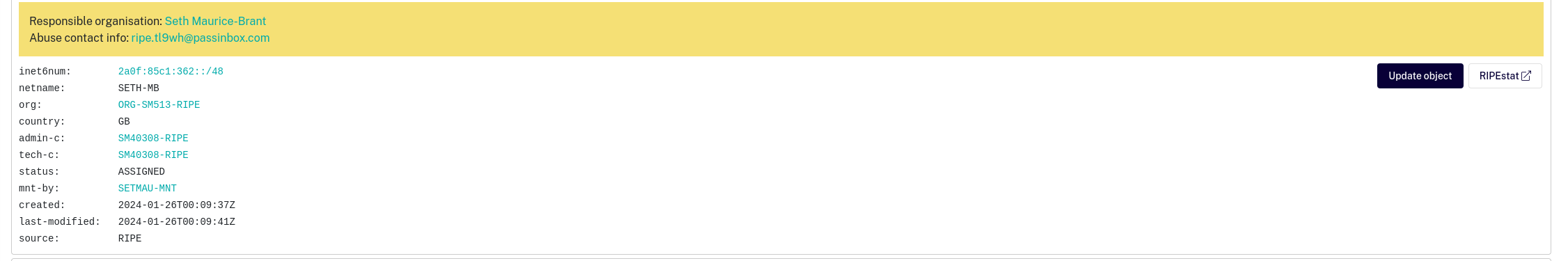

RIPE Database

- Before you can do anything with RIPE, including apply for an ASN, you have to create a few objects

- But hold on for a second, what is the RIPE database?

- In a nutshell, the RIPE database is used to

- ensure all internet routing information is unique

- allow easy access to abuse contacts for network operators

- publishing information required to make the internet work

- In a nutshell, the RIPE database is used to

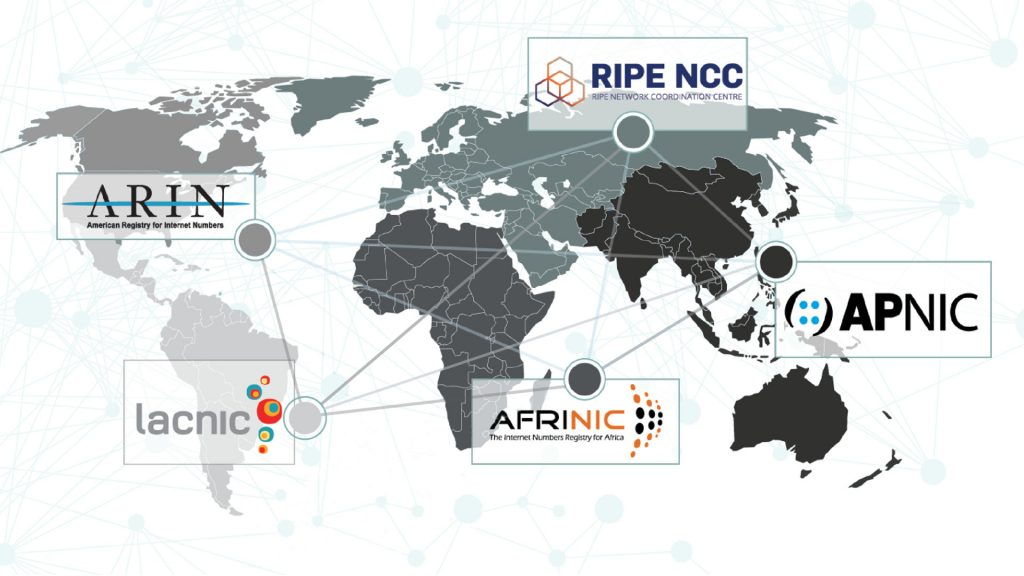

- RIPE do not have the only database in the world, and RIPE is not the only Regional Internet Registry (RIR)

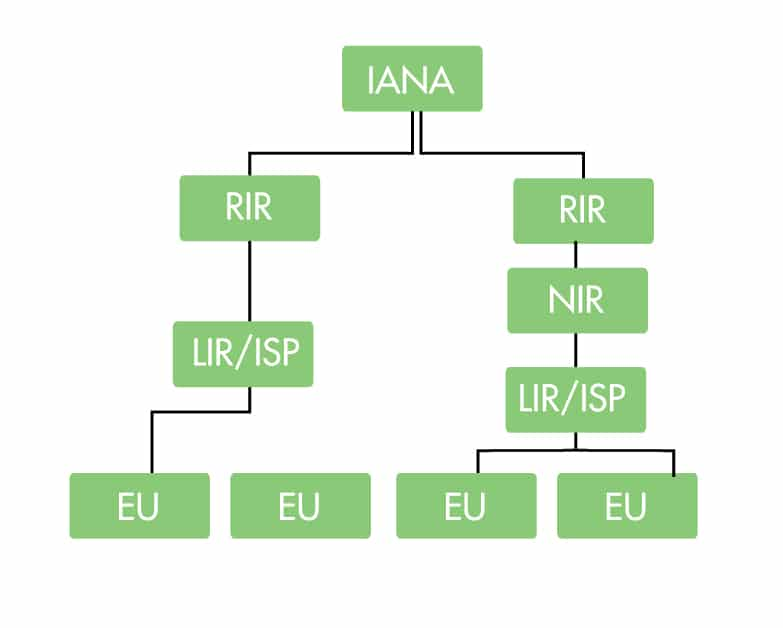

- I’m mostly working with LIRs and RIRs here, but knowing about the others involved is useful.

- IANA is globally the highest authority, they aggregate data from all RIRs

- RIRs are regionally assigned.

- LIRs and ISPs are generally service providers, and are usually fairly large organisations

- EU simply stands for end user, that’s us.

- Back to making our RIPE objects.

- First thing’s first, we need to make a

MAINTAINERand aPERSONpair. - This is required to do anything useful with the RIPE database.

BGP with BIRD

- So for those that don’t know, Bird is controlled 2 ways:

- A configuration file (typically

/etc/bird/bird.conf) - A command line utility (

birdc)

- A configuration file (typically

- The idea is you include your options in the config file and then use the command-line tool to make tweaks and verify things are doing what they’re expected to.

- So, can we see the file that caused so much pain? You sure can.

#/etc/bird/bird.conf

#

log syslog all;

router id 0.0.0.0;

# Actual server IPv4 has been replaced with 0.0.0.0 for security.

protocol static static_bgp {

ipv6;

route 2a0f:85c1:362::00/48 via 0.0.0.0;

}

protocol device {

scan time 5;

}

protocol direct {

interface "dummy*";

ipv6 {

import all;

};

}

protocol kernel {

ipv6 {

export all;

};

scan time 15;

}

protocol bgp frantech {

local as 215634; //My ASN

source address 0.0.0.0;

neighbor 1.1.1.1 as 53667; //Frantech, not their actual IP

password "secret"; //It's not actually "secret" btw

multihop 2;

ipv6 {

import none;

export where proto = "static_bgp";

};

graceful restart on;

}- When I see it here, it looks like a perfectly normal configuration file that makes sense. You might even be able to tell what it does.

- But let’s step through it, bit by bit to dissect what’s going on here.

- And for both your sanity and mine, I’m not going to go through the debugging hell I experienced here with you. The TLDR of that problem was documentation was a bit obscure and very few people talk about bird online.

router id 0.0.0.0;- This is simply defining the router IP, this should be the public IPv4 address of your server. Even if, like me, you’re using it for IPv6 routing exclusively.

protocol static static_bgp {

ipv6;

route 2a0f:85c1:362::00/48 via 0.0.0.0;

} - Here we make an instance of the

staticprotocol and assign it the namestatic_bgp - We define the channel (IPv4/IPv6) as IPv6.

- And then we say we want to route all traffic from our prefix through the router.

protocol device {

scan time 5;

} - Now we can make a device protocol and set the scan time to 5.

- This basically just allows us to get interfaces from the kernel. It’s not very exciting but it is necessary.

protocol direct {

interface "dummy*";

ipv6 {

import all;

};

} - Now we probably want to be able to send our traffic somewhere, don’t we?

- The direct protocol allows us to generate routes for all directly connected networks.

- In this example, I’m using the direct protocol to import my IP configuration.

- I have added a

dummyinterface and I have added my IPv6 prefix to that interface, so in theory any traffic bound for any IP in my range should now be received by my server.

#.bash_history

387 ip route

388 ip a add 2a0f:85c1:362::/48 dev eth0

389 ip route

482 ip link add dev dummy1 type dummy

483 ip link set dummy1 up

484 ip addr add dev dummy1 2a0f:85c1:362::/48

485 ip addr show dev dummy1protocol kernel {

ipv6 {

export all;

};

scan time 15;

} - Now we are telling the kernel about our defined IPv6 routes

- And rescanning them every 15 seconds to detect any changes.

protocol bgp frantech {

local as 215634; //My ASN

source address 0.0.0.0;

neighbor 1.1.1.1 as 53667; //Frantech, also not their actual IP

password "secret"; //It's not actually "secret" btw (or is it)

multihop 2;

ipv6 {

import none;

export where proto = "static_bgp";

};

graceful restart on; And now we’re into the juicy bit.

- This is where we define our actual bgp route.

- We have set our ASN to local as, so when we advertise a BGP route, other networks know where it is coming from.

- We force set our source address to our router, you might be able to get away with not doing this, but it’s a good idea.

- Our neighbour information was provided by Frantech, the IP is their router and the AS is, you guessed it, their ASN. We’re sending our routing information to Frantech so they can share it with the world.

- Frantech also requires a password be used to ensure that a BGP route is being advertised by the correct people.

- Multihop simply tells bird we are not directly plugged into the neighbour. The

2is optional, but I dropped it in so bird knows I’m expecting their to be 2 hops on the route between my server and the Frantech router.- I found this out using a simple

traceroute

- I found this out using a simple

traceroute to 0.0.0.0 (0.0.0.0), 30 hops max, 60 byte packets

1 1.1.1.2 (1.1.1.2) 0.142 ms 0.128 ms 0.144 ms

2 1.1.1.1 (1.1.1.1) 0.380 ms 0.352 ms 0.301 ms

- Once again, IPs are being replaced with placeholders.

- Then we define the IPv6 channel, and say that we wish to import no routes from that channel, but we wish to export all of our previously defined

static_bgproutes to Frantech. - And

graceful restartjust means a restart shouldn’t harm active connections.

And the cumulative result of this is now I can enable the bird daemon:

birdc

And check my Frantech protocol:

BIRD 2.0.12 ready.

bird> show proto all frantech

Name Proto Table State Since Info

frantech BGP --- up 2024-01-31 Established

BGP state: Established

Neighbor address: 1.1.1.1

Neighbor AS: 53667

Local AS: 215634

Neighbor ID: 1.1.1.1

Local capabilities

Multiprotocol

AF announced: ipv6

Route refresh

Graceful restart

Restart time: 120

AF supported: ipv6

AF preserved:

4-octet AS numbers

Enhanced refresh

Long-lived graceful restart

Neighbor capabilities

Multiprotocol

AF announced: ipv4 ipv6

Route refresh

Graceful restart

Restart time: 120

AF supported: ipv4 ipv6

AF preserved:

4-octet AS numbers

Enhanced refresh

Long-lived graceful restart

Session: external multihop AS4

Source address: 0.0.0.0

Hold timer: 149.664/240

Keepalive timer: 33.963/80

Channel ipv6

State: UP

Table: master6

Preference: 100

Input filter: REJECT

Output filter: (unnamed)

Routes: 0 imported, 0 exported, 0 preferred

Route change stats: received rejected filtered ignored accepted

Import updates: 0 0 0 0 0

Import withdraws: 196420 0 --- 196420 0

Export updates: 2 0 1 --- 1

Export withdraws: 0 --- --- --- 1

BGP Next hop: 2a0f:85c1:362::

IGP IPv6 table: master6- With the key information being the BGP state being

Established. Believe me when I say that took a while. We had a lot of being stuck inConnectingandSocket: Connection closed. (It turns out Stallion was blocking connections because I hadn’t enabled them)

- This needed me to set the IP addresses to my server IPs in order for BGP requests from my server to be accepted. D’uh!

RPKI

- So I had got my BGP routing working now - whoopie. However, Frantech had now informed me that as my prefixes were not RPKI signed that Stallion (their control panel) would not whitelist me.

- But why? What makes RPKI important?

- RPKI is effectively the IP equivalent of HTTPS for HTTP. (it’s not, but it does a similar job). If a BGP route is RPKI signed, then we know it actually came from the intended ASN and not someone who knows what Google’s ASN is.

- This meant I had to figure out how to sign a prefix with RPKI. Obviously my first point of contact was RIPE, as I recalled seeing an RPKI portal on RIPE.

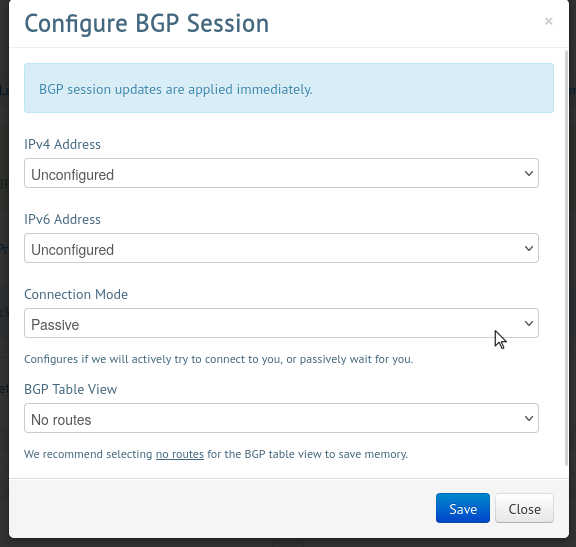

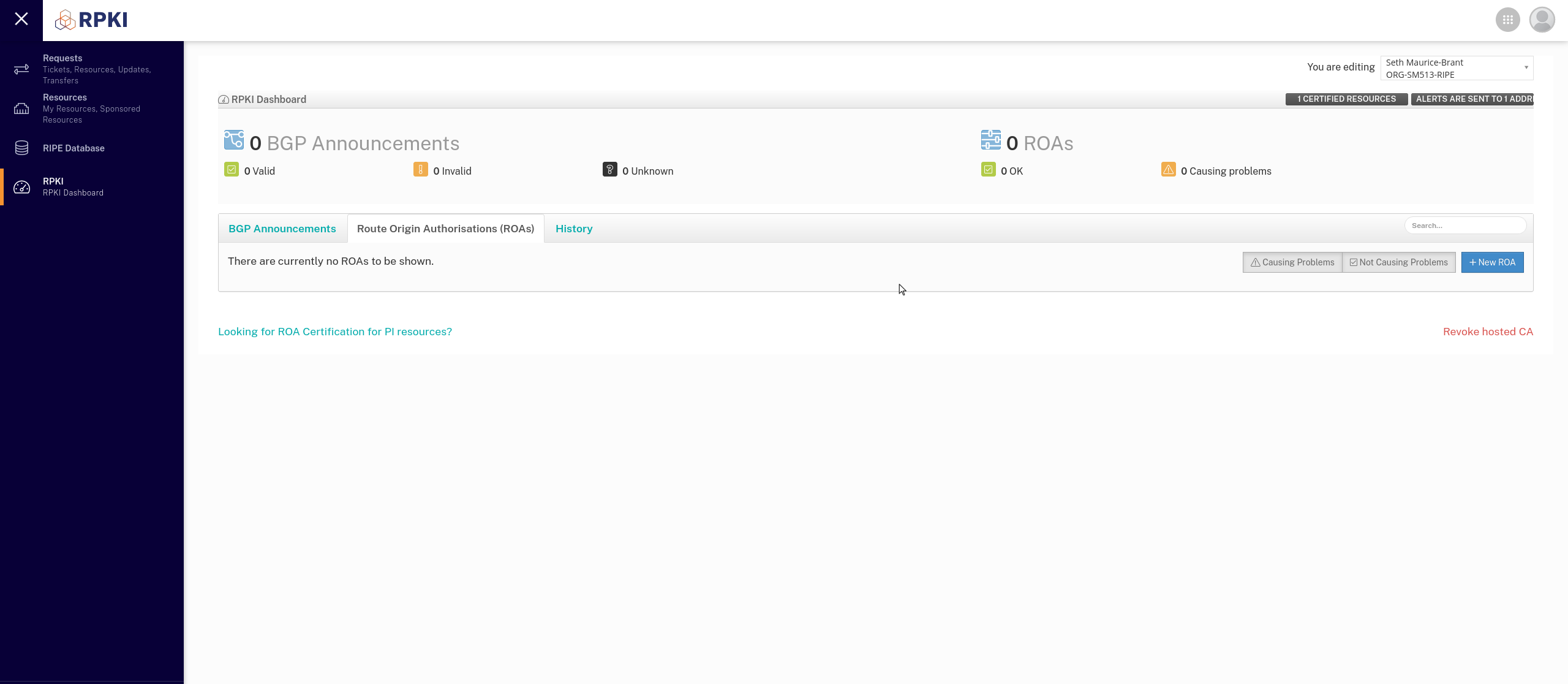

-

So I headed on over, chose for RIPE to host things for me and clicked the New ROA button.

-

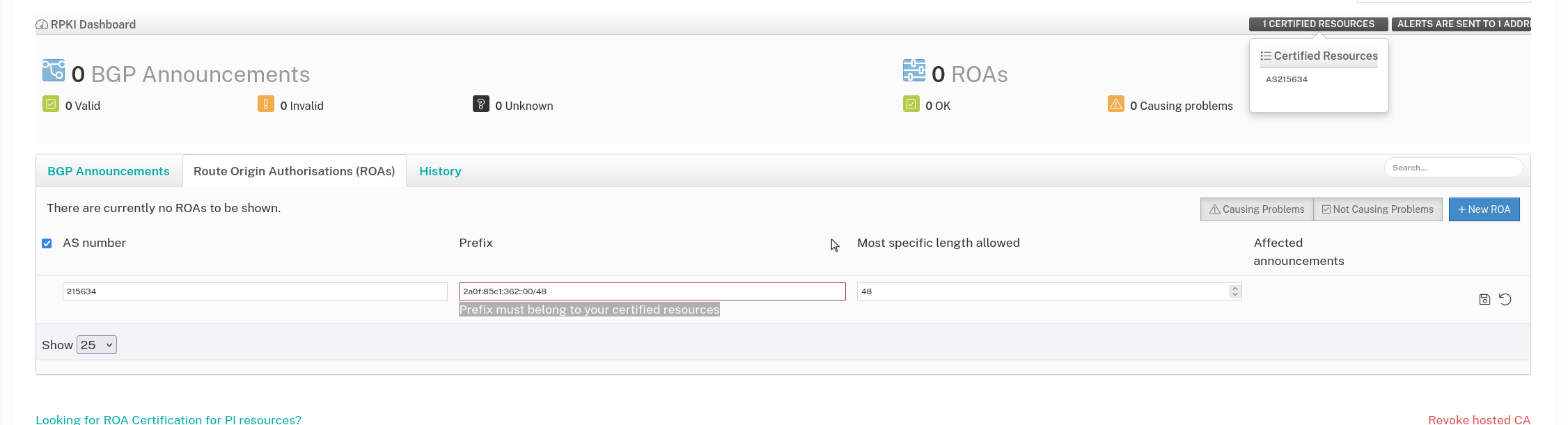

I was prompted to fill out a few fields, nothing too complex. But that’s obviously when something went wrong.

-

Ripe was reporting that the prefix I entered was not a certified resource. It was definitely my prefix though.

-

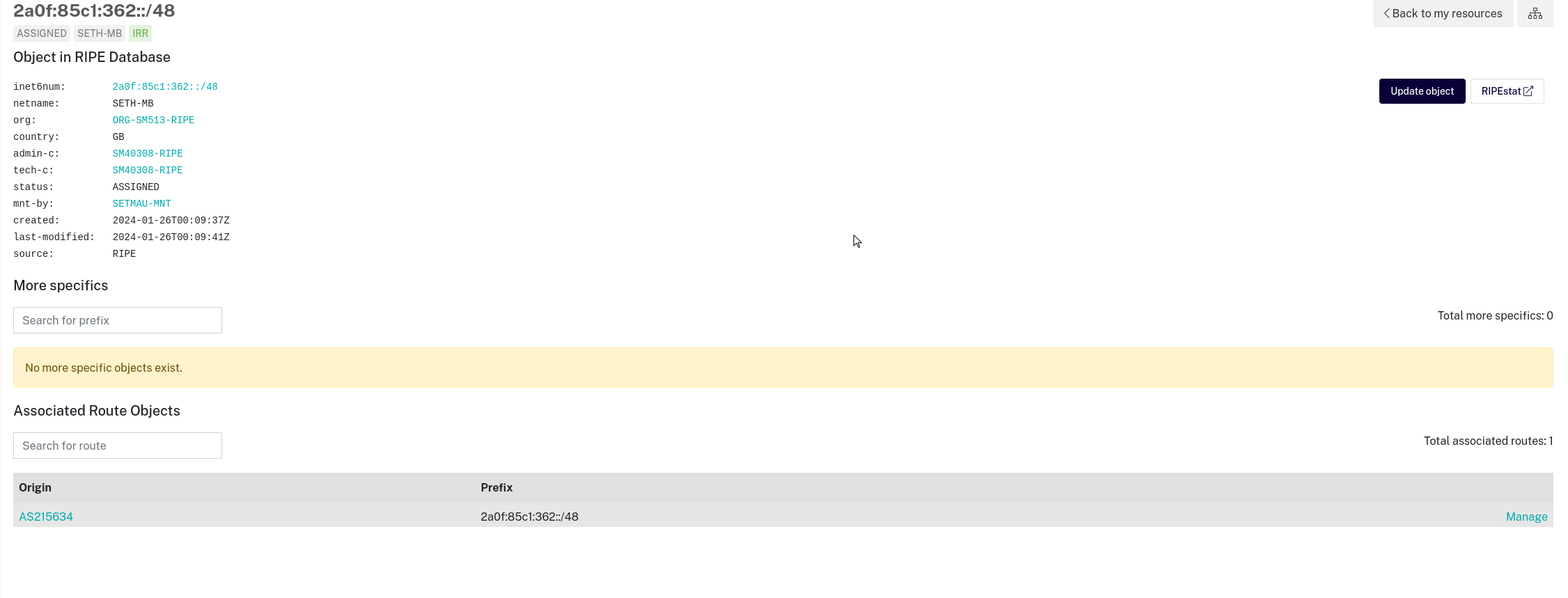

Odd, maybe I can fix this?

-

So off to create a route object I went

-

Everything seemed in order

-

So, what was wrong?

-

Well, after a bit of digging I discovered that because my IP block was PA not PI, I was unable to issue an RPKI certificate for it.

-

So that was a problem. I knew when I chose PA that I may bump into some issues because of the choice, but I didn’t really expect this one.

-

RPKI signing remained very important as I did want my route to be advertised.

-

So, I had to contact Lagrange Cloud as my sponsoring LIR they would probably know what to do.

-

I spoke with Nate from Lagrange, who was fast to reply and helpful as always. He said that there were two options, I could either have them configure the RPKI route for me or I could run my own Krill server.

-

Now I had just been presented with a shall we do this the easy way? or shall we do this the hard way?

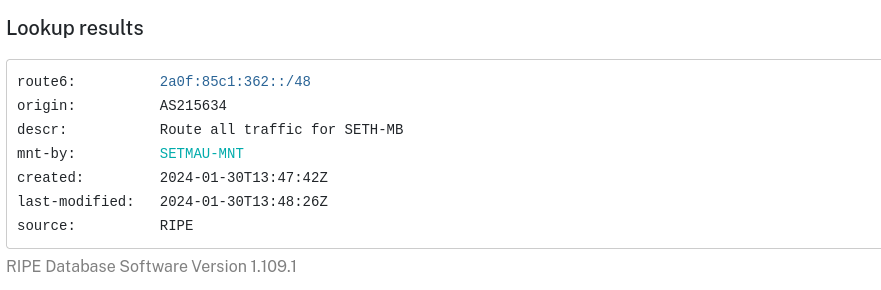

Krill

- So fast forward a bit and here I am trying to setup a krill server.

- Thankfully, this seemed to be documented well.

- I quickly installed a Krill server on my Debian server for BGP announcements and started it up.

- Annnndddd… nothing.

- Restart it?

- Nothing…

- One more time?

- Aaaannnddd red text.

Feb 01 06:34:58 localhost systemd[1]: krill.service: Start request repeated too quickly.

Feb 01 06:34:58 localhost systemd[1]: krill.service: Failed with result 'signal'.- A very nice, descriptive error that told me exactly what was wrong. If only.

- I figured something definitely wasn’t working as intended, so I spent a few minutes flicking over the Krill docs,

/etc/krill.confand my Cloudflare setup. I even tried installed Nginx and setting up a reverse proxy to serve Krill (maybe it was silently failing because there was no builtin webserver?) - To make matters slightly worse, log files were not generating, so I couldn’t find any more info.

- But then I considered the fact that I was using a 512MB RAM server, so maybe that wasn’t enough. I ran

dmesg | grep oom-killerto check for any issues with memory, and bingo.

[870792.057996] dhclient invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[870804.049696] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[870838.678977] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140dca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP|__GFP_ZERO), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[870850.692584] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[870863.052492] dockerd invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=-500

[870875.469858] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[870888.570205] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[870901.654079] bgpd invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871225.405321] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871237.353661] systemd-journal invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=-250

[871249.558336] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871261.743526] sshd invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871274.089660] systemd-journal invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=-250

[871707.255636] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140dca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP|__GFP_ZERO), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871721.056659] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140cca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871733.417554] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140dca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP|__GFP_ZERO), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871745.248140] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140dca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP|__GFP_ZERO), order=0, oom_score_adj=0

[871757.346486] krill invoked oom-killer: gfp_mask=0x140dca(GFP_HIGHUSER_MOVABLE|__GFP_COMP|__GFP_ZERO), order=0, oom_score_adj=0- Krill needed more memory. Now I wasn’t particularly prepared to fork out any more money for a server, even though this one was only ≅$2.40/mo. So it was off to find one of my other servers that I could run Krill on.

- I found a server in my house with enough free RAM and installed Krill on that - no problems.

- But this server didn’t have any graphical interface, so I would still need that nginx reverse proxy.

- Unfortunately as this was a multipurpose server, running mostly with docker containers I couldn’t just run nginx normally, as port 80 was not up for grabs.

nginx[3642274]: nginx: [emerg] bind() to 0.0.0.0:80 failed (98: Address already in use)- Port 80 turned out to just be a blank apache server, so we gutted that and ran our Nginx config again.

server {

server_name my.magickrill.org;

# not my actual hostname

client_max_body_size 100M;

location / {

proxy_pass https://localhost:3000/;

# krill runs on port 3000 by default, no point changing that

}

listen 80;

# We could use a different port, but 80 is nice.

}- And just like that, we had Krill.

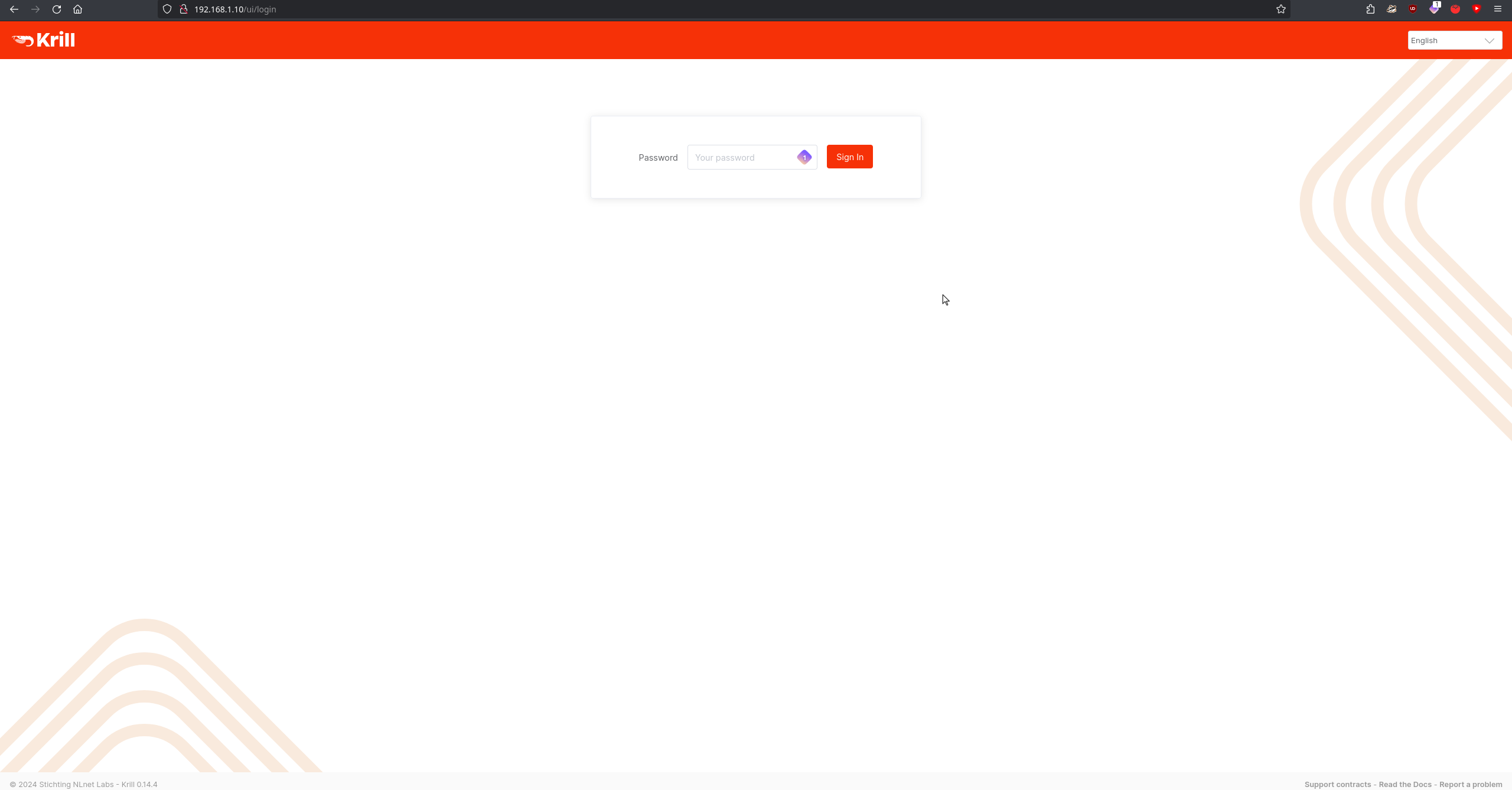

- A simple

sudo cat /etc/krill.conf | grep admin_tokenand we had our password. - Next step was to make myself a certificate authority, I chose the inventive

SETH-MBname and moved on. - However I still had my hosted CA on RIPE, so I had to go and revoke that before I could continue.

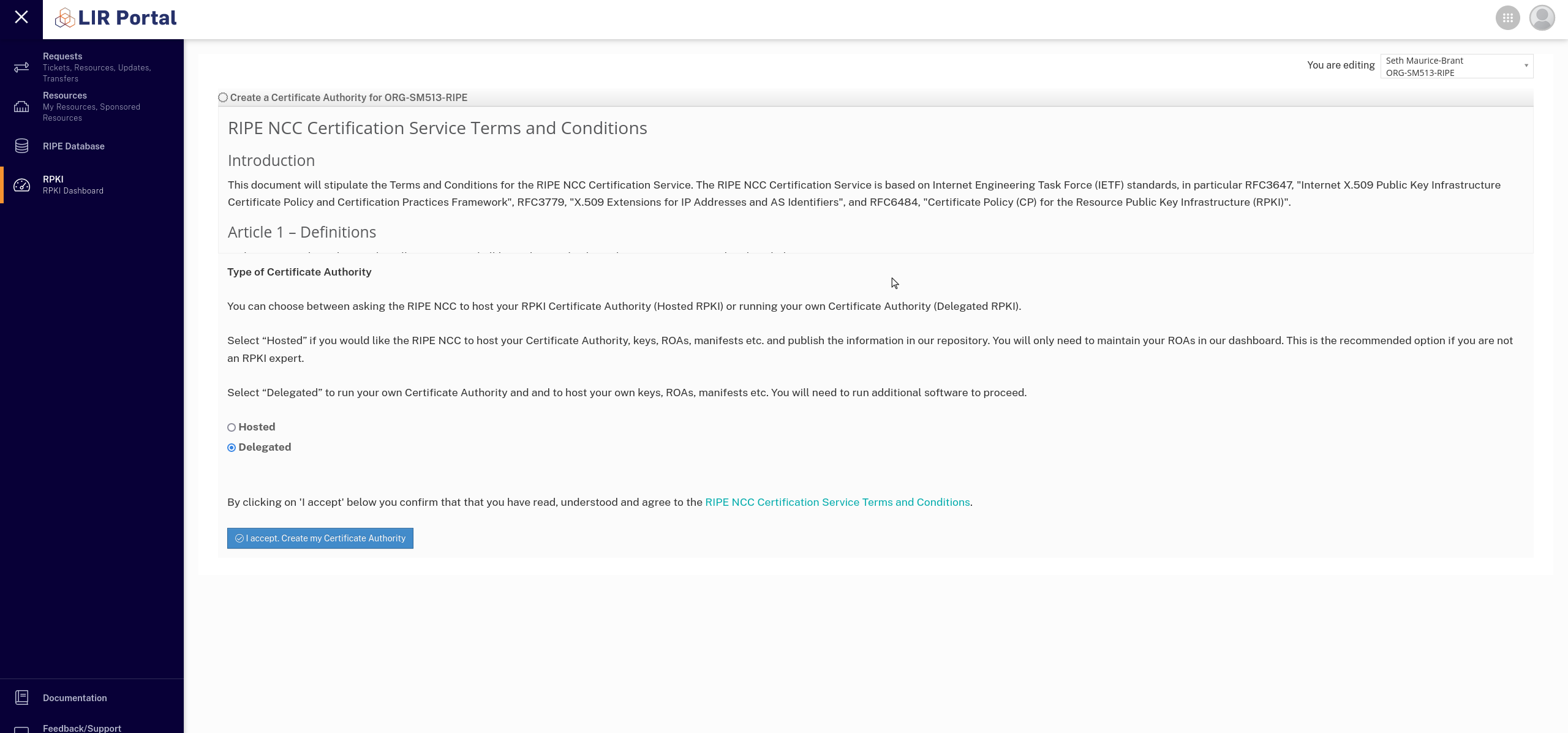

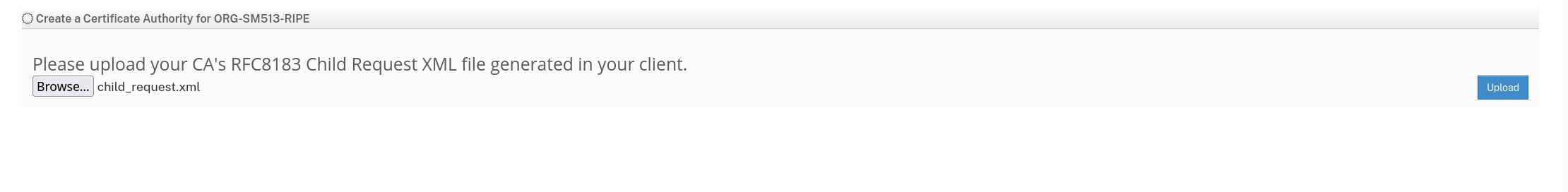

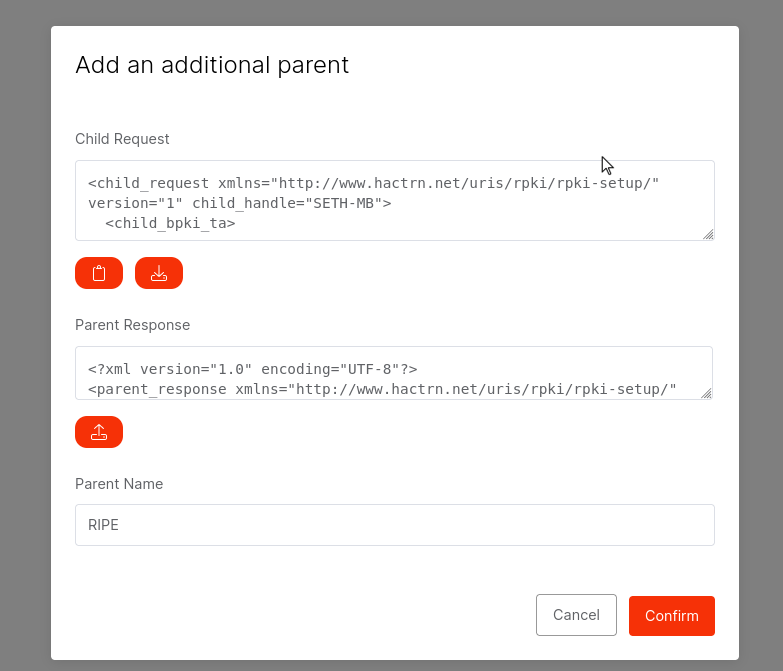

- Now I could make a delegated CA under RIPE and generate a child request XML file from Krill to link myself up.

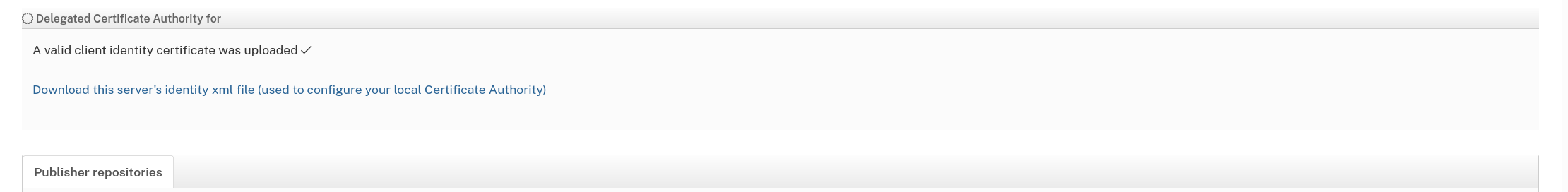

- Now let’s go and stick the generated server identity file into Krill.

- Parent added, now we needed to make a repository.

- I won’t bore you with the details because it’s basically the same process I’ve just gone through again, nothing too interesting happened here.

- I decided then to reach out to Lagrange as my ROA certification wasn’t working, and I likely needed them to delegate access to me.

- Lagrange took another child request and had to forward it to their upstream provider to get me a parent request.

- I had to sign off for a bit here, as I couldn’t proceed until the parent request was back, so I took some time to work on another one of my caffeine fuelled madnesses.

Success!

Once RPKI routes were published, my routes started propagating to Frantech’s peers.

If your network has IPv6 support, you can connect to a little nginx webserver I have running on the router at https://route0.sethmb.xyz

There is also an interactive tool from RIPE here to let you see a visualisation of BGP interactions.

Future Plans

I would quite like to stop relying on the Frantech server at some point. For this, I would run a Raspberry Pi on my home network and publish BGP announcements from there. This is limited however as my ISP does not allow BGP announcements (I asked) so I would need to use BGP over GRE and partner up with someone like https://tunnelbroker.net/ to get this working. Further investigation required!